Chapter3

Models, Layers and Activations

In this chapter, we will introduce how to organize the components of neural network models.

0. Setups for this section

import time

import pandas as pd

import tensorflow as tf

from functools import reduce

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

from pprint import pprint

print(tf.__version__)

tf.random.set_seed(42)

true_weights = tf.constant(list(range(5)), dtype=tf.float32)[:, tf.newaxis]

x = tf.constant(tf.random.uniform((32, 5)), dtype=tf.float32)

y = tf.constant(x @ true_weights, dtype=tf.float32)

2.1.0

1. Models

A model is a set of parameters and the computation methods using these parameters. Since these two elements are tied together, we could organize them better by encapsulating the two into a class.

Recall our linear regression model. Its parameters and computation are as follows:

weights = tf.Variable(tf.random.uniform((5, 1)), dtype=tf.float32)

y_hat = tf.linalg.matmul(x, weights)

We can write a simple class to do the job.

class LinearRegression(object):

def __init__(self, num_parameters):

self._weights = tf.Variable(tf.random.uniform((num_parameters, 1)), dtype=tf.float32)

@tf.function

def __call__(self, x):

return tf.linalg.matmul(x, self._weights)

@property

def variables(self):

return self._weights

Note that we decorated the __call__ method with tf.function, hence a graph will be generated to back up the computation.

With this class, we can rewrite the previous training code as:

model = LinearRegression(5)

@tf.function

def train_step():

with tf.GradientTape() as tape:

y_hat = model(x)

loss = tf.reduce_mean(tf.square(y - y_hat))

gradients = tape.gradient(loss, model.variables)

model.variables.assign_add(tf.constant([-0.05], dtype=tf.float32) * gradients)

return loss

t0 = time.time()

for iteration in range(1001):

loss = train_step()

if not (iteration % 200):

print('mean squared loss at iteration {:4d} is {:5.4f}'.format(iteration, loss))

pprint(model.variables)

print('time took: {} seconds'.format(time.time() - t0))

mean squared loss at iteration 0 is 18.7201 mean squared loss at iteration 200 is 0.0325 mean squared loss at iteration 400 is 0.0017 mean squared loss at iteration 600 is 0.0002 mean squared loss at iteration 800 is 0.0000 mean squared loss at iteration 1000 is 0.0000 <tf.Variable 'Variable:0' shape=(5, 1) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[-3.1365452e-03], [ 1.0065703e+00], [ 2.0000944e+00], [ 3.0032609e+00], [ 3.9934685e+00]], dtype=float32)> time took: 0.40303897857666016 seconds

Here, we still decorated the train_step function with tf.function. The reason is that the loss and gradient calculation can also benefit from graphs.

This simple model class works fine. But it can be better if we subclass from tf.keras.Model.

class LinearRegression(tf.keras.Model):

def __init__(self, num_parameters, **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

self._weights = tf.Variable(tf.random.uniform((num_parameters, 1)), dtype=tf.float32)

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

return tf.linalg.matmul(x, self._weights)

This model class has a few differences compare with the organic version. First is that we implemented the call method rather than the dunder version of it. Under the hood, tf.keras.Model’s __call__ method is a wrapper over this call method, and it is performing, among many other things, things like converting inputs to tensors and graph building. The second thing is that we dropped the accessor for the variables because we inherited one.

With this subclass model, we need to modify the training code a bit to make it work. The .variables accessor from tf.keras.Model gives us a collection of references to the model’s variables, to accommodate complex models with many sets of variables. So, as a result, the corresponding gradients will be a collection too.

model = LinearRegression(5)

@tf.function

def train_step():

with tf.GradientTape() as tape:

y_hat = model(x)

loss = tf.reduce_mean(tf.square(y - y_hat))

gradients = tape.gradient(loss, model.variables)

for g, v in zip(gradients, model.variables):

v.assign_add(tf.constant([-0.05], dtype=tf.float32) * g)

return loss

t0 = time.time()

for iteration in range(1001):

loss = train_step()

if not (iteration % 200):

print('mean squared loss at iteration {:4d} is {:5.4f}'.format(iteration, loss))

pprint(model.variables)

print('time took: {} seconds'.format(time.time() - t0))

mean squared loss at iteration 0 is 18.7201 mean squared loss at iteration 200 is 0.0325 mean squared loss at iteration 400 is 0.0017 mean squared loss at iteration 600 is 0.0002 mean squared loss at iteration 800 is 0.0000 mean squared loss at iteration 1000 is 0.0000 [<tf.Variable 'Variable:0' shape=(5, 1) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[-3.0575476e-03], [ 1.0064486e+00], [ 2.0001044e+00], [ 3.0031927e+00], [ 3.9935682e+00]], dtype=float32)>] time took: 0.39172911643981934 seconds

Through subclassing tf.keras.Model, we get to use many methods from it, like print out a summary and the Keras model training/testing methods.

print(model.summary())

model.compile(loss='mse', metrics=['mae'])

print(model.evaluate(x, y, verbose=-1))

Model: "linear_regression" _________________________________________________________________ Layer (type) Output Shape Param # ================================================================= Total params: 5 Trainable params: 5 Non-trainable params: 0 _________________________________________________________________ None [4.27835811933619e-06, 0.0016658232]

Let’s also try using the .fit API to train our linear regression model.

model = LinearRegression(5)

model.compile(optimizer='SGD', loss='mse')

model.optimizer.lr.assign(.05)

t0 = time.time()

history = model.fit(x, y, epochs=1001, verbose=0)

pprint(history.history['loss'][::200])

pprint(model.variables)

print('time took: {} seconds'.format(time.time() - t0))

[19.127595901489258, 0.02714746817946434, 0.0010814086999744177, 6.190096610225737e-05, 6.568436219822615e-06, 1.0572820201559807e-06] [<tf.Variable 'Variable:0' shape=(5, 1) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[-1.2103192e-03], [ 1.0031627e+00], [ 2.0000432e+00], [ 3.0014870e+00], [ 3.9966750e+00]], dtype=float32)>] time took: 1.2371714115142822 seconds

Not surprisingly we recovered the ground truth, but it took significantly more time compared to our custom training loop, it is probably due to the convenient .fit API is doing a bunch more stuff than updating parameters.

Now, let’s spice up the model a bit by adding a additional useless bias term and initialize it with a large value. Ideally, after training, this bias term would become an insignificantly small number.

class LinearRegressionV2(tf.keras.Model):

def __init__(self, num_parameters, **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

self._weights = tf.Variable(tf.random.uniform((num_parameters, 1)), dtype=tf.float32)

self._bias = tf.Variable([100], dtype=tf.float32)

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

return tf.linalg.matmul(x, self._weights) + self._bias

model = LinearRegressionV2(5)

t0 = time.time()

for iteration in range(1001):

loss = train_step()

pprint(model.variables)

[<tf.Variable 'Variable:0' shape=(5, 1) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[0.95831835], [0.01680839], [0.3156035 ], [0.16013157], [0.7148702 ]], dtype=float32)>, <tf.Variable 'Variable:0' shape=(1,) dtype=float32, numpy=array([100.], dtype=float32)>]

Hmm, something is very wrong, the bias term is not updated at all. Guess where might be the problem? It’s in the train_step function. Since the input signature has not changed(there is none), the function is been lazy and did not realize it should do a retracing. Thus it is training with the old graph, in which the bias term simply does not exist!

To address this issue, we can make model as an input to train_step, so that when the function is invoked with a different model it will create or grab a graph accordingly.

@tf.function

def train_step(model):

with tf.GradientTape() as tape:

y_hat = model(x)

loss = tf.reduce_mean(tf.square(y - y_hat))

gradients = tape.gradient(loss, model.variables)

for g, v in zip(gradients, model.variables):

v.assign_add(tf.constant([-0.05], dtype=tf.float32) * g)

return loss

model = LinearRegression(5)

for iteration in range(1001):

loss = train_step(model)

pprint(model.variables)

model = LinearRegressionV2(5)

for iteration in range(5001):

loss = train_step(model)

pprint(model.variables)

print(train_step._get_tracing_count())

[<tf.Variable 'Variable:0' shape=(5, 1) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[-3.4687696e-03], [ 1.0070834e+00], [ 2.0001261e+00], [ 3.0035236e+00], [ 3.9930055e+00]], dtype=float32)>] [<tf.Variable 'Variable:0' shape=(5, 1) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[-2.6756483e-03], [ 9.9403673e-01], [ 1.9959891e+00], [ 2.9956400e+00], [ 3.9983556e+00]], dtype=float32)>, <tf.Variable 'Variable:0' shape=(1,) dtype=float32, numpy=array([0.00964569], dtype=float32)>] 2

We see that Tensorflow traced two graph for our training function, one for each model.

2. Layers

We typically use the Model class for the overall model architecture, that is how may combine many smaller computational units to do the job. It is ok to code up small units with tf.keras.Model and then combine them, but since we won’t really need many of the model specific functionalities with these smaller building blocks(for example, its unlikely we would ever want to call the .fit method on a unit). It is better to use the tf.keras.layers.Layer class. Actually, the Model class is a wrapper over the Layer class.

Lets say that we want to ‘upgrade’ the linear regression model to be a composition of a few linear transformations. We can code up the linear transformation as a Layer class and then just combine a bunch of its instances of it them in one model.

class Linear(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, num_inputs, num_outputs, **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

self._weights = tf.Variable(tf.random.uniform((num_inputs, num_outputs)), dtype=tf.float32)

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

return tf.linalg.matmul(x, self._weights)

class Regression(tf.keras.Model):

def __init__(self, num_inputs_per_layer, num_outputs_per_layer, **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

self._layers = [Linear(num_inputs, num_outputs)

for (num_inputs, num_outputs) in zip(num_inputs_per_layer, num_outputs_per_layer)]

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

for layer in self._layers:

x = layer(x)

return x

In Linear class definition above, we swapped the super class and generalized it with the option to specify output size. In the Regression model class, we have the option to use one or a chain of this Linear layers. One obvious benefit with this set up, is that we now separated the concern of how individual computing units should work and the overall architecture design of the model. We use Layer to handle the first, and use Model to tackle the latter.

Let’s see if the model is trainable.

model = Regression([5, 3], [3, 1])

for iteration in range(1001):

loss = train_step(model)

print('Mean absolute error is: ', tf.reduce_mean(tf.abs(y - model(x))).numpy())

Mean absolute error is: 1.2218952e-06

One problem with this linear layer is that it needs the complete sizing information and allocates resources for all the variables upfront. Ideally, we want it to be a bit lazy, it should calculate variable sizes and occupy resources only when needed. To archive this, we implement the build method which will handle the variable initialization. The build method can be explicitly called, or it will be invoked automatically the first time there is data flow to it. With this, the constructor now only stores the hyperparameters for the layer.

class Linear(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, units, **kwargs):

super(Linear, self).__init__(**kwargs)

self.units = units

def build(self, input_shape):

self._weights = self.add_weight(shape=(input_shape[-1], self.units))

super().build(input_shape)

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

output = tf.linalg.matmul(x, self._weights)

return output

class Regression(tf.keras.Model):

def __init__(self, units, **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

self._layers = [Linear(unit) for unit in units]

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

for layer in self._layers:

x = layer(x)

return x

model = Regression([3, 1])

pprint(model.variables) # should be empty

for iteration in range(1001):

loss = train_step(model)

print('Mean absolute error is: ', tf.reduce_mean(tf.abs(y - model(x))).numpy())

pprint(model.variables)

[] Mean absolute error is: 8.5681677e-07 [<tf.Variable 'linear_2/Variable:0' shape=(5, 3) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[ 0.31275296, -0.34405178, 0.3254243 ], [-0.00516788, 0.7107771 , 0.00381865], [ 1.0885493 , 0.08547033, 0.54993755], [ 1.5066153 , 0.12321236, 0.01402206], [ 1.1230973 , 1.2026962 , -0.6002657 ]], dtype=float32)>, <tf.Variable 'linear_3/Variable:0' shape=(3, 1) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[ 1.8777134 ], [ 1.4221834 ], [-0.30101135]], dtype=float32)>]

Tensorflow has a lot of layer options, we will cover a sample of them in later application specific chapters. For now, we will just quickly see if the linear layer(called Dense) from Tensorflow works the same.

class Regression(tf.keras.Model):

def __init__(self, units, **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

self._layers = [tf.keras.layers.Dense(unit, use_bias=False) for unit in units] # the only change

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

for layer in self._layers:

x = layer(x)

return x

model = Regression([3, 1])

for iteration in range(1001):

loss = train_step(model)

print('Mean absolute error is: ', tf.reduce_mean(tf.abs(y - model(x))).numpy())

pprint(model.variables)

Mean absolute error is: 1.206994e-06 [<tf.Variable 'dense/kernel:0' shape=(5, 3) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[ 0.3859551 , -0.5379335 , -0.3105871 ], [-0.3746996 , -0.28152603, 0.45071942], [ 1.0012726 , -0.08671893, 0.7469904 ], [ 0.2887405 , -0.875283 , 1.0489686 ], [ 0.43472984, -0.5105482 , 1.6707851 ]], dtype=float32)>, <tf.Variable 'dense_1/kernel:0' shape=(3, 1) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[ 0.41473213], [-0.86908275], [ 2.020607 ]], dtype=float32)>]

Indeed, it is working as expected.

3. Activations

So our newest model is a composition of two linear transformation, but the composition of two linear transformations is just another linear transformation.

reduced_model = reduce(tf.linalg.matmul, model.variables)

print(reduced_model)

print(tf.reduce_all(tf.abs(model(x) - x @ reduced_model) < 1e-6))

tf.Tensor( [[2.2053719e-06] [9.9999624e-01] [1.9999999e+00] [2.9999964e+00] [4.0000048e+00]], shape=(5, 1), dtype=float32) tf.Tensor(True, shape=(), dtype=bool)

Without anything interesting in between, this is just adding unnecessary complexity. The simplest thing to do is to add some non-linear in-place transformation to the intermediate results, and this is call activations.

Let’s add activations as layers.

class ReLU(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

return tf.maximum(tf.constant(0, x.dtype), x)

class NeuralNetwork(tf.keras.Model):

def __init__(self, units, last_linear=True, **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

layers = []

n = len(units)

for i, unit in enumerate(units):

layers.append(Linear(unit))

if i < n - 1 or not last_linear:

layers.append(ReLU())

self._layers = layers

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

for layer in self._layers:

x = layer(x)

return x

model = NeuralNetwork([3, 1])

for iteration in range(1001):

loss = train_step(model)

print('Mean absolute error is: ', tf.reduce_mean(tf.abs(y - model(x))).numpy())

pprint(model.variables)

reduced_model = reduce(tf.linalg.matmul, model.variables)

print(reduced_model)

print(tf.reduce_any(tf.abs(model(x) - x @ reduced_model) < 1e-6))

Mean absolute error is: 0.005225517 [<tf.Variable 'linear_4/Variable:0' shape=(5, 3) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[ 0.10789682, -0.31562465, -0.00532613], [-0.05060532, -0.46457097, 0.42605096], [-0.61450577, 0.45144582, 0.8922052 ], [ 0.439215 , -0.59760475, 1.2671946 ], [ 0.36582235, 0.14377609, 1.7026857 ]], dtype=float32)>, <tf.Variable 'linear_5/Variable:0' shape=(3, 1) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[ 0.13811348], [-0.3345939 ], [ 2.3246977 ]], dtype=float32)>] tf.Tensor( [[0.10812643] [1.138893 ] [1.8381848 ] [3.206461 ] [3.960648 ]], shape=(5, 1), dtype=float32) tf.Tensor(False, shape=(), dtype=bool)

With our underline ground truth to be a simple linear model, the added non-linear activations is not really helpful, and in fact it made the optimization harder.

Since activation functions usually follows immediately after linear transformations, we can fuse them together, so that the model code can be simpler.

class Linear(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, units, use_bias=True, activation='linear', **kwargs):

super(Linear, self).__init__(**kwargs)

self.units = units

self.use_bias = use_bias

self.activation = activation

def build(self, input_shape):

self._weights = self.add_weight(shape=(input_shape[-1], self.units))

if self.use_bias:

self._bias = self.add_weight(shape=(self.units), initializer='ones')

super().build(input_shape)

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

output = tf.linalg.matmul(x, self._weights)

if self.use_bias:

output += self._bias

if self.activation == 'relu':

output = tf.maximum(tf.constant(0, x.dtype), output)

return output

class NeuralNetwork(tf.keras.Model):

def __init__(self, units, use_bias=True, last_linear=True, **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

layers = [Linear(unit, use_bias, 'relu') for unit in units[:-1]]

layers.append(Linear(units[-1], use_bias, 'linear' if last_linear else 'relu'))

self._layers = layers

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

for layer in self._layers:

x = layer(x)

return x

model = NeuralNetwork([3, 1])

for iteration in range(1001):

loss = train_step(model)

print('Mean absolute error is: ', tf.reduce_mean(tf.abs(y - model(x))).numpy())

pprint(model.variables)

Mean absolute error is: 0.0075564235 [<tf.Variable 'linear_6/Variable:0' shape=(5, 3) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[ 0.13394988, 0.51800126, 0.09352156], [-0.15037392, 0.25468782, 0.49990052], [-0.69800115, -0.42260593, 0.8586105 ], [-0.08989831, -0.33655766, 1.2849052 ], [ 1.0911363 , -0.32361698, 1.6646731 ]], dtype=float32)>, <tf.Variable 'linear_6/Variable:0' shape=(3,) dtype=float32, numpy=array([ 0.5917124, 0.5500173, -0.576148 ], > dtype=float32)>, <tf.Variable 'linear_7/Variable:0' shape=(3, 1) dtype=float32, numpy= array([[ 0.14004707], [-0.45114964], [ 2.2325916 ]], dtype=float32)>, <tf.Variable 'linear_7/Variable:0' shape=(1,) dtype=float32, numpy=array([1.4508461], dtype=float32)>]

There are also many activation functions we can choose from that ship with Tensorflow. We will do a survey on them later.

4. Fully Connected Networks

With the code above, we just made a fully connected network, or historically called multi layer perceptron(with out any actual perceptron) as well as feed forward neural network. Its essentially a sequence of linear transformation with in-place non-linear activations sandwiched in between. We usually think of the initial layers as feature extractors that is performing some kind on implicit feature engineering and selection, and think of the last layer as a regressor or classifier per task.

Note how we are using a list to host the layers and applying them sequentially in the call method. Lets quickly implement a quality of life improvement model class called Sequential to do this. It is pretty much a water down version of tf.keras.Sequential.

class Sequential(tf.keras.Model):

def __init__(self, layers, **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

self._layers = layers

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

for layer in self._layers:

x = layer(x)

return x

class MLP(tf.keras.Model):

def __init__(self, num_hidden_units, num_targets, hidden_activation='relu', **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

if type(num_hidden_units) is int: num_hidden_units = [num_hidden_units]

self.feature_extractor = Sequential([tf.keras.layers.Dense(unit, activation=hidden_activation)

for unit in num_hidden_units])

self.last_linear = tf.keras.layers.Dense(num_targets, activation='linear')

@tf.function

def call(self, x):

features = self.feature_extractor(x)

outputs = self.last_linear(features)

return outputs

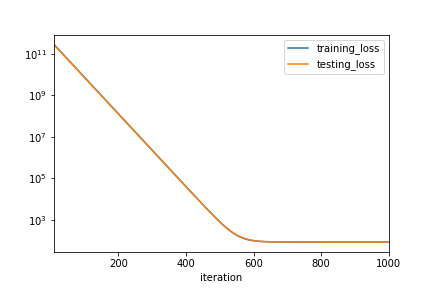

Let’s try to apply our MLP model to a real regression problems: the boston housing dataset shipped with Tensorflow. The dataset is splitted into two sets, a training set and a testing set. We will train the model on training set only, but record the loss on both sets to see if the reduction in training set loss is inline with reduction in the unseen testing set.

(x_tr, y_tr), (x_te, y_te) = tf.keras.datasets.boston_housing.load_data()

y_tr, y_te = map(lambda x: np.expand_dims(x, -1), (y_tr, y_te))

x_tr, y_tr, x_te, y_te = map(lambda x: tf.cast(x, tf.float32), (x_tr, y_tr, x_te, y_te))

@tf.function

def train_step(model, x, y):

with tf.GradientTape() as tape:

loss = tf.reduce_mean(tf.square(y - model(x)))

gradients = tape.gradient(loss, model.variables)

for g, v in zip(gradients, model.variables):

v.assign_add(tf.constant([-0.01], dtype=tf.float32) * g)

return loss

@tf.function

def test_step(model, x, y):

return tf.reduce_mean(tf.square(y - model(x)))

def train(model, n_epochs=1000, his_freq=10):

history = []

for iteration in range(1, n_epochs + 1):

tr_loss = train_step(model, x_tr, y_tr)

te_loss = test_step(model, x_te, y_te)

if not iteration % his_freq:

history.append({

'iteration': iteration,

'training_loss': tr_loss.numpy(),

'testing_loss': te_loss.numpy()

})

return model, pd.DataFrame(history)

mlp, mlp_history = train(MLP(4, 1))

pprint(mlp_history.tail())

ax = mlp_history.plot(x='iteration', kind='line', logy=True)

fig = ax.get_figure()

fig.savefig('ch3_plot_1.png')

95 960 84.622253 83.714134 96 970 84.622231 83.713562 97 980 84.622299 83.713020 98 990 84.622231 83.712601 99 1000 84.622269 83.712318

It may seem that our model has nicely converged. Since there is not much a discrepancy between training set and testing set performance. However if we look at the numbers more closely, they are pretty bad. A simple constant prediction have MSE around 83. What could go wrong? We will look at other optimizers in the next chapter.

print(tf.reduce_mean(tf.square(y_te - tf.reduce_mean(y_te))))

tf.Tensor(83.24384, shape=(), dtype=float32)